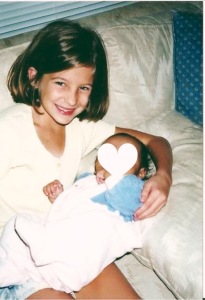

I was eight-years-old when I said goodbye to my first foster sibling. She had lived in our home for only 40 days, but it felt as if she had always been a part of our family walks and read-aloud mornings by the fireplace. She came to us with each leg secured in a cast, working day and night to hold together broken bones and provide stability for cracked ribs. Six weeks later, we were madly in love with a baby, and that baby was being stripped away by the vulnerability associated with love. She left our home with strengthened legs, kicking and flailing like babies should. That part was good. But still, she left.

We drove her to the office where a caseworker was waiting in the parking lot to carry her off to her next new home. I kept bending down, reaching under her car seat straps, to kiss her over and over again. It was my first bitter taste of loss in this life. I now know her story had a happier ending than it did beginning, but still, she was living in our home, riding in our minivan, filling our washing machine with laundry, sucking on bottles in the middle of the night, healing from broken bones, learning to trust humanity again – and then, with what felt like no fair warning, she was gone and never seen again.

That loss (and the subsequent losses of the many foster siblings that followed) was profoundly formative in my heart’s fight for growth.

I find it fascinating that the human heart is only capable of grieving to the extent that the brain has progressed physiologically. It’s as if we have these mile markers that only allow an eight-year-old to grieve with the expression and understanding that is appropriate for that tender, missing teeth, messy hair, molding heart, stage of life. Then, the next mile marker comes into sight and the now twelve-year-old child can revisit the traumatic event with a new, deeper level of understanding. As children, we have these deeply formative life events, that leave us crying and hurting and angry and sad, and yet, our hearts have this ferocious resiliency so that it is only through the appropriate passage of time that we are able to safely grapple with and process the full extent of the tears of our childhood. This is how the heart was made, to grieve carefully and methodically, because if a child starts the race of grief too fast, there may be burn-out, and suddenly, the finish line’s view is obstructed by social delay, behavioral outbursts, and developmental regression.

My saving grace is that during my years of loving and letting go over and over again, I was held by parents who listened to me cry into the deepest pockets of the night, planned a fun outing to distract us immediately after a foster child left, answered questions about drugs and abuse, fed me ice-cream, and allowed me to feel whatever emotion my heart needed to feel.

What happened through all of these moments is that I was safely able to process the circumstances taking place in our home, and my heart was able to find room to expand as it grasped with greater understanding the acts of injustice that are repeatedly inflicted onto those who are the most vulnerable. So that then, when a few of those kids stayed in our home, turning temporary siblings into forever siblings, I was maybe a tiny bit more equipped to empathetically enter into their pain.

Not that I can begin to understand the fires of trauma that my siblings have walked through, but maybe, because my parents allowed me to enter into the care of the many foster children that lived with us, I am better able to stand ahead at each mile marker, armed with an ice-cream date or a spontaneous trip to our favorite bookstore, ready to fight off the attacks that accompany the perils of the grief and healing journey.

They pass these markers with chocolate-stained faces and a few extra “I love yous” tucked safely in their pockets. I watch them keep running. They are passing mile markers, sometimes in a sprint and other times slowing to a walk, championing through their journey with so much courage that it astounds me.

As an eight-year-old, long before I ever knew I would be a big sister, I grieved the loss of a baby who had enough resilience left to trust, even after acts of horror had been inflicted on her. The irony is that as I said goodbye to one who had fought to heal, I had no idea that our hearts are capable of withstanding storms; that the immediate pain we feel can be used to cultivate a level of trust and passion and pursuit, used to contribute a little bit of safety to the hearts around us that are also journeying through grief.

That the cries of our heart and the running- stumbling- across the finish line are achieving an eternal weight of glory that far outweighs even the hardest goodbye.

_______________________

Kylee is a college student who is passionately pursuing a degree in Social Work while simultaneously learning what it means to be a big sister to kids from “hard places”. Her parents jumped into the crazy world of foster care just days before her 8th birthday for numerous infants and toddlers over a ten year time span; four of those children became permanent family members through adoption. Kylee loves sharing about foster care and adoption and is passionate about advocating on behalf of vulnerable children on her blog Learning to Abandon.